Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs)

You may have read about a new drug type available for certain cancers called “antibody-drug conjugates” or ADCs. But what exactly are these drugs and how do they work?

What is an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC)?

Traditional chemotherapy causes lots of side effects because the active drug impacts all your cells without discriminating between healthy cells and cancer cells.

ADCs are a type of targeted cancer treatment that has been designed to deliver a chemotherapy drug directly into the inside of the cancer cells.

By only releasing the chemotherapy drug inside the cancer cells and not to healthy cells, this means that a lower dose of a more powerful chemotherapy can be used.

So how does an ADC work?

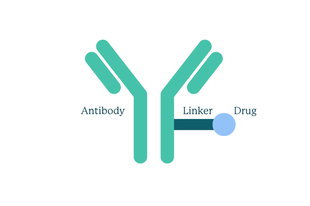

The ADC is made up of three parts:

How an ADC is made up

- The monoclonal antibody: a lab-made antibody that looks for and targets a specific protein on the surface of cancer cells. When the antibody binds to the protein, like a key into a lock, this makes the cell open the door to allow the drug inside.

- A potent chemotherapy drug: This is delivered directly into the cancer cell itself and then destroys it.

- Linker molecules: These attach the chemotherapy to the antibody and only break this link when the drug is inside the cancer cell. This helps make sure the drug is targeted only at the cancer cells.

Does an ADC work on every type of cancer?

Each type of ADC is designed to target a particular protein found on a specific type of cancer cell. Even within a tumour that has been found to have this protein on its surface, it may be that not every cancer cell carries it.

In this case, some of the chemotherapy drug can seep out to reach other cancer cells that are nearby so can still help kill more of the tumour. However, for the drug to work as designed, the tumour must have a certain level of the antibody that the ADC targets on the surface of the cancer cells.

This is why your tumour will need to be tested to find out if you are able to take a particular ADC.

Do ADCs cure cancer?

ADCs are used for people whose cancer has returned (recurred) or has become resistant to traditional chemotherapy. The goal isn’t to cure their cancer, but to offer more time without the cancer returning or progressing.

What types of ADC are available?

There are ADCs already available in the UK for certain cancers, including breast cancer (e.g. Trodelvy) and blood cancers (e.g. Blenrep).

The first ADC that has been granted marketing authorisation for ovarian cancer, and is currently being assessed by NICE in England, is Elahere (Mirvetuximab soravtansine). This drug targets a protein called folate receptor alpha (FRα) on the surface of the ovarian cancer cells. To read more about Elahere and how it works, see below.

Are other types of ADC on the horizon?

Research is going on across the world into how these drugs can be used in many cancer types, and to create new types of ADCs.

There are over 300 ADCs now being testing in clinical trials. These drugs all target different proteins, and research is looking into finding options with the best effectiveness with lowest or least serious side effects.

Elahere (Mirvetuximab soravtansine)

What is Elahere?

Elahere is the brand name of Mirvetuximab soravtansine, and is an antibody- drug conduit (ADC). It is a targeted treatment for certain ovarian cancer patients.

Who is eligible for Elahere?

Elahere was granted marketing authorisation by UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in July 2025 specifically for women with advanced high-grade serous ovarian, fallopian tube or primary peritoneal cancer, whose cancer is folate receptor-alpha positive and who are now platinum-resistant after one to three previous treatments.

This means it is for women with this subtype of ovarian cancer who have tried platinum chemotherapy and their cancer has come back or progressed within a timeframe that indicates they are no longer responding to the chemotherapy. Their tumour must also test positive for high expression of the folate receptor-alpha protein. It is currently being assessed by NICE to decide whether it will be funded by the NHS in England for these patients.

Take a look at more information about how the drug approvals process works.

What tests do I have to have to see if I am eligible to get Elahere?

The antibody used in Elahere attaches to a protein called folate receptor-alpha (FRα) on the surface of the ovarian cancer cells. The Elahere can then get inside the cancer cell to deliver a chemotherapy drug called DM4 which kills the cell.

For the drug to work as it is meant to, the tumour must have a high level of the protein that the ADC targets on the surface of the cancer cells. To find this out, a sample of your tumour is tested by pathologists in a lab. Your tumour is considered FRα positive if over 75% of the cancer cells have moderate to high amounts of the protein on their surface (called FRα-high expression).

Roughly 80% of recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer has FRα on the surface of its cancer cells, and approximately 32%-36% of ovarian cancer cells have FRα-high expression12.

How is Elahere given?

Elahere is given intravenously (via a drip) over 2-4 hours, once every three weeks. The first infusion usually takes 1.5-3 hours, but after that the treatment should only take around 1-2 hours. You may also be given some medications to help reduce possible reactions and side effects (see examples of possible side effects below).

What are the benefits of Elahere?

The MIRASOL study compared Elahere to standard chemotherapy in platinum-resistant patients. The results suggested that Elahere helped extend the time before the cancer spread or grew (this is known as “median progression-free survival”) from 4 months to 5.6 months.

It also helped some people live longer, with a median overall survival of 16.5 months compared to 12.7 months. This means the time point at which 50% of patients were still alive.

The study found that more people’s tumours responded to the drug compared to traditional chemotherapy. Specifically, for 37% of people in the group taking Elahere, their tumour shrank by at least 30%. In the traditional chemotherapy group, this level of response was seen in only 16% of people. In the Elahere group, 5% of people had no signs of cancer on their follow-up scan, whereas no people had this result in the chemotherapy group.

What are the side effects of Elahere?

The most common side effect is eye problems, affecting 56% of people who use Elahere. These include:

- Dry eyes

- Blurred vision

- Changes to the cornea

- Sensitivity to light

- Eye pain or irritation

Eye problems typically started around five weeks after starting the treatment, between the second and third infusion. In the MIRASOL trial, eye problems caused 2% of patients to stop taking Elahere.

Elahere causes some similar side effects to a standard chemotherapy, including:

- Nausea/ vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Fatigue

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Decreased liver enzymes

- Decreased red/white blood cell counts

- Decreased platelets

There is also a small chance (10%) of developing a type of lung inflammation called pneumonitis.

Hair loss is not a side effect of Elahere.

What can be done to prevent eye issues?

It’s recommended that patients have their eyes examined before starting Elahere, and also take preventative measures including using prescribed eye drops regularly, avoiding contact lenses and using sunglasses.

Eye health will be actively monitored by the clinical team and patients are asked to highlight any changes as soon as possible.

If you do have eye problems, it may be possible to interrupt (take a planned pause in treatment) or reduce the dose to see if this helps. Most of the eye changes people have return to normal or improve when dose changes are made or the eye issues are treated.

What about other ovarian cancer patients?

The GLORIOSA trial has been looking at platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients, and comparing the effect of taking Avastin (bevacizumab) alone with a separate group taking both Avastin and Elahere. This phase 3 study has finished recruiting patients but in the next few years we will start to learn whether this combination may be effective in this patient group.

The PICCOLO trial was a phase 2 trial looking at the safety and efficacy of Elahere in platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients, and showed some promising results in this group. More research is needed before we know if this will be an option in the future.

Check out our page for information on clinical trials and how to get involved.