What is a genetic fault (aka genetic mutation)?

What are genetic faults (aka genetic mutation)?

Our genes are like instructions that tell our bodies how to work. They help make proteins, which are the building blocks of our body. Think of genes as a manual that tells your body what to do.

Why do genetic faults matter?

A genetic fault (also known as a genetic mutation or alteration) is like a spelling mistake in that manual, changing how it works. These changes can increase your risk of getting cancer.

For example, everyone has BRCA (Breast Cancer) genes, which we get from our parents. These genes help fix damaged cells and stop them from growing too fast.

If there’s a mutation in these genes, they can’t do their job, and cells can grow out of control. This can increase the risk of breast and ovarian cancer.

What is Lynch syndrome?

Lynch syndrome is a condition that makes some people more likely to get certain cancers, including colorectal, ovarian, and uterine cancer. It’s caused by mutations in genes like MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2, and EPCAM. Normally, these genes help stop cancer from developing, but mutations mean they can’t do their job properly.

What are the risks of a genetic fault?

The tables below show the estimated lifetime risk (up to age 70) for these genetic mutations:

BRCA

| Population | BRCA1 | BRCA2 | |

| Ovarian cancer risk to age 80 | 2% | 44% (risk increases from age 40) | 17% (risk increases from mid-late 40s) |

| Breast cancer in unaffected women to age 80 | 14% | 72% | 69% |

| Male breast cancer risk to age 80 | 0.4% | 4% | |

| Prostate cancer risk to age 85 | 18% | Similar to population risk | 41% |

| Pancreatic cancer risk to age 80 | 2% | Similar to population risk | Men 3%, women 2% |

The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, A Beginner’s Guide to BRCA1 and BRCA2, December 2023, accessed September 2024

Lynch syndrome

| Male | Female | |||

| Lifetime risk | General population | Lynch syndrome carrier | General population | Lynch syndrome carrier |

| Colorectal | 7% | up to 57% | 6% | up to 48% |

| Ovarian | - | - | 2% | up to 17% |

| Womb | - | - | 3% | up to 49% |

| Upper gastrointestinal | 5% | up to 22% | 4% | up to 13% |

| Ureter/kidney | 3% | up to 18% | 2% | up to 19% |

| Bladder | 2% | up to 13% | <1% | up to 18% |

| Brain | <1% | up to 8% | <1% | up to 3% |

| Prostate | 18% | up to 24% | - | - |

The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, A Beginner’s Guide to Lynch syndrome, Accessed September 2024

Other faulty genes

Other genes can also increase the risk of ovarian cancer, like RAD51C, RAD51D, BRIP1, PALB2, and STK11. There are still many genes we don’t know enough about yet, but researchers are learning more every day.

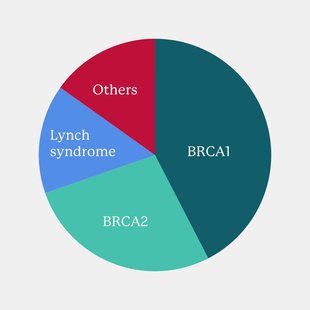

Figure 1: Susceptibility genes and their prevalence in hereditary ovarian syndromes (Adapted from Angela Toss, Chiara Tomasello, Elisabetta Razzaboni, Giannina Contu, Giovanni Grandi, Angelo Cagnacci, Russell J. Schilder, Laura Cortesi, "Hereditary Ovarian Cancer: Not Only BRCA 1 and 2 Genes", BioMed Research International, vol. 2015, Article ID 341723, 11 pages, 2015)

How common are genetic faults (aka genetic mutations)?

Most cases of breast and ovarian cancer are not due to genetic mutations. Around 20% of all cases of ovarian cancer are due to an inherited gene fault such as BRCA1/2 or Lynch syndrome.

About 1 in 200 people have a BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene fault. This number is higher in some groups, like people with Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, where it’s 1 in 40.

Lynch syndrome is less common, affecting about 1 in 250 people.*

* The International Society for Gastrointestinal Hereditary Tumours (InSiGHT) Accessed September 2024

Passing on genetic faults (aka genetic mutations)

If you have a mutation in BRCA1, BRCA2, or a Lynch syndrome gene, there is a 50% chance you could pass it on to your children. You only need one faulty copy of the gene to increase your cancer risk. The only way to know for sure is to get a genetic test.

Important things to remember

- A genetic mutation means a higher risk, not a guarantee of cancer.

- Men can inherit and pass on these mutations just like women.

- You can get these mutations from either parent and pass them on whether you are a man or a woman.

Why get tested?

Knowing your BRCA status can help you get the right treatment if you have ovarian cancer. It also helps prevent future cases in your family. Here are some things to think about:

- Preventative options like surgery and extra check-ups could reduce ovarian cancer cases by about 20%, or 1,500 cases a year.

- If you have a BRCA mutation, other family members are at risk of carrying the same high risk.

- Testing positive means you can warn family members so they can get tested if they want.

- If you have a BRCA gene fault or Lynch syndrome, you have a 50% chance of passing it to your children.

Everyone has the right to choose whether to get tested. It’s an important decision, and genetic counseling can help you decide.

For more about BRCA mutations, click here.

For more about Lynch Syndrome, visit www.lynch-syndrome-uk.org.