QI Methodology

There are several tools and methods described in the QI literature and it’s important to choose the correct one for your project. This section walks you through selecting the best method and explains the formal QI methods that have been adopted in healthcare and how to use the discipline of project management to ensure effective QI.

QI Organisational Approaches:

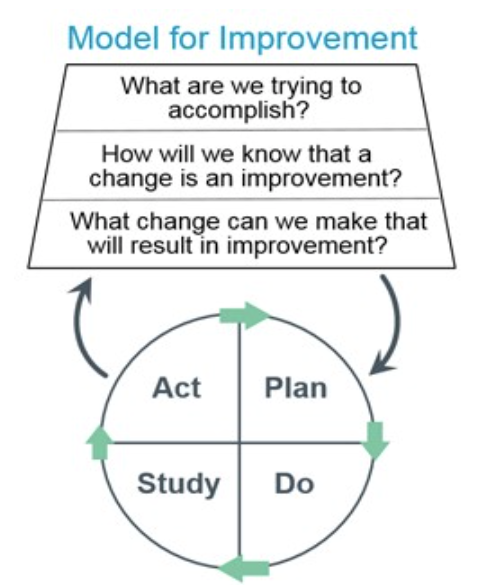

1 The Model for Improvement and PDSA cycles:

The Model for Improvement and the PDSA (Plan-Do-Study-Act) cycle have been championed in healthcare by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) https://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/default.aspx

The Model for Improvement is a straightforward yet powerful tool for quality improvement for ovarian cancer care. Imagine you want to reduce patient waiting times for treatment.

First, you'd ask, "What are we trying to accomplish?" This sets your aim. Next, you measure how long patients currently wait. Now, you're ready for a PDSA cycle. You 'Plan' a change, like a new scheduling system. You 'Do' by implementing it on a small scale. 'Study' the results—did wait times reduce?

Finally, you 'Act' on the data of the small-scale test by either adopting the change more widely or revising your plan in response to what the data shows about deficits in the approach. These quick cycles let you test improvements in real-time, making your care services better step-by-step

It has been noted in improvement research that PDSAs are often carried out with too little emphasis on the ‘Study’ stage of the cycle. It is important that you are clear at the outset how you will measure the results of the change you have implemented at the ‘Do’ stage. Another common mistake in implementing this model is that the results from one PDSA cycle are not used to make tweaks to how the improvement idea has been implemented. The team quickly move onto the next, unrelated idea to test.

HICO Project: A Case Study on the Use of PDSA Cycles Overview:

The HICO project aimed to holistically improve the treatment and care for older women with ovarian cancer. An essential part of its methodology was the Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycle. Across two cycles, the project recruited 46 patients in the first and adjusted processes for the second, based on real-world data and feedback.

Why PDSA Worked:

The PDSA cycle is designed for quick, iterative changes, making it an excellent fit for healthcare settings where conditions and needs are complex as in ovarian cancer care. For instance, after the first PDSA cycle, patient engagement scores improved by 25%, and a 15% improvement was seen in functional metrics related to physiotherapy interventions. This real-time, quantitative feedback enabled the team to make targeted adjustments for the second cycle, embodying the continuous improvement spirit of PDSA.

Challenges and Mitigations:

Despite its effectiveness, the HICO project encountered challenges such as understaffing, which led to a 20% slower recruitment rate initially, and limited time for stakeholder engagement. The PDSA model allowed for quick adaptations. For example, stakeholder feedback from the first cycle led to a 30% reduction in the time needed for assessments (information engagement, processes and therapy approaches) by the second cycle. This rapid adjustment would be particularly appealing to clinicians dealing with resource constraints.

Conclusion:

The use of PDSA cycles in the HICO project provided not just a framework for improvement but also real, measurable outcomes. The iterative nature of PDSA, demonstrated by improvements in patient engagement and functional metrics, proved valuable for continuous improvement. Despite initial challenges, the project saw significant advancements, including quicker assessment times and improved patient metrics.

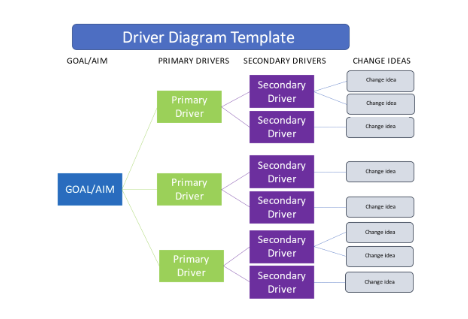

Driver Diagrams:

Driver diagrams are a foundational tool in the field of Quality Improvement (QI). They visually map out the relationship between an improvement aim and the factors, or 'drivers’, that influence it.

Think of it as a roadmap for improvement efforts, helping teams to clearly articulate their aim, identify primary and secondary drivers affecting the outcome, and outline potential interventions.

This visual layout fosters a shared understanding among team members and stakeholders, aligning everyone's efforts. Commonly used in the planning phase, driver diagrams are dynamic and can be updated as teams learn more, ensuring ongoing refinement of improvement strategies.

The driver diagram visualizes the hierarchy of tasks and subtasks needed to complete an objective. It helps to organize theories and ideas when planning an improvement effort. A Driver Diagram is made up of:

- Goal/Aim: the problem to be addressed and what are you trying to achieve.

- Primary Drivers: aim to drive the improvement of the main goal, may include major processes, operating rules, or structures that will contribute to moving towards the aim

- Secondary Drivers: elements that feed into the Primary Drivers. The secondary drivers are most likely to be the areas where action will help to reach the project aim.

- Change ideas: Actionable ideas to test where changes can lead to improvements related to the Secondary Drivers.

A simple template for a driver diagram:

Find out more about how to develop and use a driver diagram to help plan your QI project with this toolkit from Health Innovation West of England: Driver Diagram Toolkit

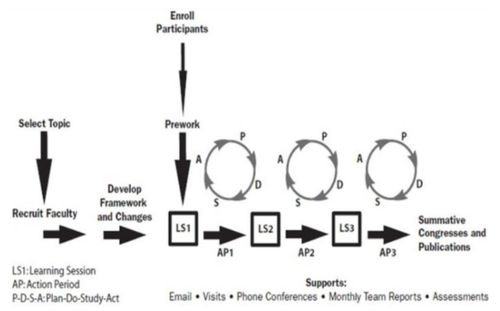

Breakthrough Collaboratives:

Breakthrough Collaboratives are another method pioneered by the IHI. They aim to bring teams together to work on agreed issues with a common approach, so that they join together for initial learning and planning sessions and then share progress, as the work is implemented.

The model suggests at least three joint learning and sharing sessions over a period of about a year, with ‘action periods’ between the learning sets where each team implements the initiative in their service.

A Breakthrough Collaborative can bring ovarian cancer clinicians together to quickly drive big improvements in patient care.

Think of it as a teamwork accelerator: multiple teams tackle the same issue, like improving early diagnosis rates, and then share what works and what doesn't. It's a fast-track to better practices.

In the NHS environment, the primary aim is often to find solutions that can be scaled up across the healthcare system. However, be cautious. The NHS is large and complex, so what works in one area may not easily transfer to another. Time and resources can also be hurdles, as achieving 'breakthrough' results often requires a dedicated effort.

The Breakthrough Series: IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2003. (Available on www.IHI.org)

The Lean Method

Lean is a Quality Improvement approach originally from the manufacturing sector but adapted for healthcare settings. It aims to streamline operations and eliminate waste, including any low value steps in a process.

For example, in a hospital setting, Lean could identify inefficient steps in the process of preparing a patient for surgery, like redundant checks or idle time waiting for an operating room and propose solutions to eliminate them.

The benefit of Lean is that it often leads to faster, more cost-effective care without compromising quality.

However, there are limitations. Lean primarily targets operational efficiencies, so it may not fully address issues related to the complexity and variability of medical care. Overzealous application can lead to resource cuts that compromise quality, so it's crucial to maintain a balanced approach.

Follow this link to access the NHS guide to lean in Healthcare: Going Lean in the NHS

The NHS has invested in a major programme to implement Lean across five trusts, working with the Virginia Mason Institute, the US healthcare organization which has led the way for Lean in healthcare. Read the evaluation here

TQM Total Quality Management

In NHS cancer centres, Total Quality Management (TQM) is a holistic approach aimed at long-term improvement of patient care.

It involves everyone, from senior leadership to clinical staff, focusing on meeting patient needs through continuous improvement.

Key elements include data-driven decision-making, employee involvement, and optimising both clinical and administrative processes.

The goal is to elevate the entire system, not just individual parts. However, its comprehensive nature means implementation can be time-consuming and may necessitate a shift in organisational culture. Despite these challenges, TQM's focus on overall excellence makes it a valuable approach.

More useful links to information on a range of quality improvement approaches can be found from:

HQIP Guide to quality improvement methods

https://www.hqip.org.uk/resource/guide-to-quality-improvement-methods/#.ZAy8w3bP23B

THIS Institute elements of improving quality and safety in healthcare